The Humboldt 35

Why does Humboldt County have the highest rate of missing persons reports in the state?

By Linda Stansberry [email protected] @lcstansberry[

{

"name": "Top Stories Video Pair",

"insertPoint": "7",

"component": "17087298",

"parentWrapperClass": "fdn-ads-inline-content-block",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

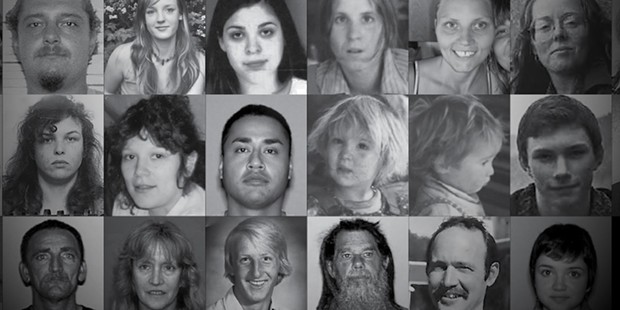

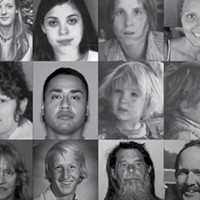

They have been missing since 1977, or just since last November. They range in age from 1 to 94. They are men and women, and two very small girls. The sheriff's office will not call any of them "cold cases" but many of their names and faces have long since slipped from public recognition. They are not the "Humboldt Five" profiled in the sensationalist 2016 Crime Watch Daily piece with Chris Hansen, which suggested a serial killer was somehow connected to the disappearances of five young women between 1993 and 2014 and referred to Humboldt County as "a lonely stretch of foggy California coastline [that] some think of as a doorway to Heaven on Earth — others as a gateway to Hell." They are the Humboldt 35 — all of the names on the California Attorney General's database of missing persons as of Jan. 18. They are identified with mugshots or grainy photos that have been digitally aged by decades. According to Journal research, Humboldt has the highest per-capita rate of people reported missing in California. Is Humboldt County, as Hansen suggested, a black hole? The answer is complicated.

To begin with, it's hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison of Humboldt to other parts of the state or other parts of the country. According to a Journal analysis of available AG data, we do have a high rate of missing persons reports. Between 2000 and 2016, we averaged 717 missing persons reports a year (both adults and children) per 100,000 residents. The statewide average? 384. It's worth noting that California has one of the most liberal standards for filing a missing persons report, with no waiting period or jurisdictional restrictions.

"It's a fallacy that it has to be 24 hours," says Lt. Dennis Young of the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office, adding that he thinks the AG numbers are "askew."

"We always take the report, we never delay it," says Sgt. Diana Freese, one of the HCSO's four detectives who work missing persons cases. "If someone calls from Humboldt County and says someone is missing in New York, I will take the report then contact the New York office for them."

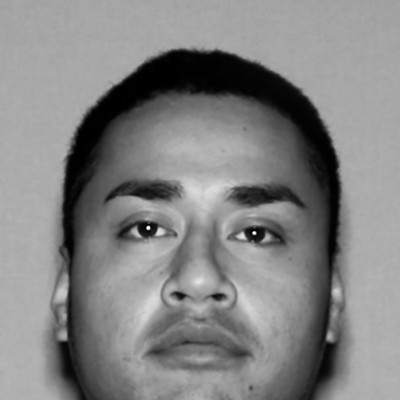

There is not a one-to-one ratio of reports to missing persons as some are reported missing multiple times, generating multiple reports. But most are not missing for long. Of the 313 reports filed for missing adults in Humboldt County in 2016, the vast majority were closed: 230 returned or were located, three were found dead, 15 arrested, eight were declared "voluntary missing," five were marked withdrawn, one marked "unknown" and 51 classified as "other," which includes suspicious circumstances. Of those 51 people, only one remains on the AG's website: Mitchell Hernandez, a 47-year-old man who walked out of a family member's home near Rancho Sequoia in Alderpoint the day before Thanksgiving, reportedly while carrying a .40 caliber pistol and a backpack. The backpack was found next to the Eel River near Fort Seward. Hernandez, described as possibly having mental health issues, remains missing.

Humboldt County ranks sixth in the state per capita for missing children reports between 2010 and 2016. One factor that may contribute to that ranking is the high number of Humboldt County children in transitional and foster care. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), these kids are at a higher risk to be chronic runaways, with each separate incident generating its own report. It has only been mandatory for states to report runaway foster youth to law enforcement and to NCMEC since 2014, thanks to an anti-sex trafficking bill passed under the Obama administration, although the Humboldt County Department of Social Services has followed this protocol since 2000. The number of annual reports for missing children in Humboldt County has hovered in the mid-600s to upper-700s for more than a decade. From 2000 through 2016, Humboldt County saw an average of 490 missing children reports annually for every 100,000 residents compared to the state average of 280.

Asked whether these disproportionate numbers put Humboldt County on NCMEC's radar, Bob Lowery, the organization's vice-president, says, in short, "No."

"It's a bit curious as to why that might be," Lowery tells the Journal in a phone interview. "It could be that the county sheriff and local police are very aggressive in accepting reports and getting them into the system. I'm not aware of any critically missing children in Humboldt County. If you dig into those number a little deeper, the reports are generally going to be runaway children."

Lowery emphasizes that 378 missing children reports filed do not necessarily represent 378 separate children, as some may be chronic runaways.

"Sometimes we've found when numbers are a little bit skewed there are reporting errors," he says. "Children who go missing typically come back in the first few days but don't always come out of system."

Both the Eureka Police Department and Humboldt County Sheriff's Office seem to agree with this assessment, saying that the majority of runaway juvenile cases are resolved within days or weeks. But according to the Journal's analysis of data available from the AG's office over the last six years, we also outpace the state average for children missing under "unknown circumstances." Statewide, runaways account for about 95 percent of missing children reports, while that percentage dips to 90 in Humboldt.

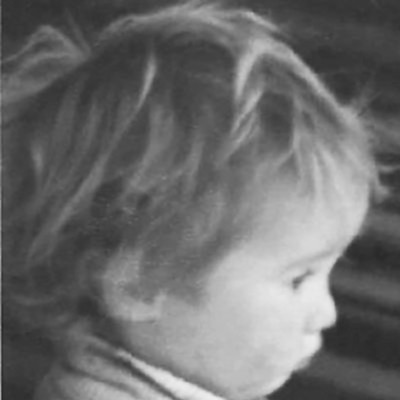

Only two children appear on the AG's list of missing persons for Humboldt County, Jessie and Fannie Stuart, ages 2 and 1 when they disappeared along with their mother, Mary Stuart, in December of 1977. Mary, who lived on a rural homestead in Honeydew, had driven into town on Dec. 10 to buy groceries and do laundry. Neither she nor the children were ever seen again, although the family's red station wagon was found on a logging road nearby. The Humboldt County District Attorney's Office reopened the case in 2009, saying it had new leads, according to an article in the Times-Standard. Byron Stuart, Mary's husband, remains the primary suspect in the case. Neighbors describe him as violent, erratic and often armed with guns. He died in 1996 and his homestead has since been subdivided, the site of many different cannabis grow scenes in the intervening decades. Although NCMEC continues to digitally age the photographs of tiny Jessie and Fannie Stuart, investigators seem to agree that they have been long since deceased.

"We never stop looking," says Young. "Investigations will stall. There comes a point in time in a lot of cases where the leads just dry up."

The only other missing juvenile case from Humboldt County that remains on NCMEC's database is Karen Mitchell, who disappeared as a teenager from U.S. Highway 101 on Nov. 25, 1997. A poster with an age-progressed picture of Mitchell, who would now be 37, still hangs on the wall of the Eureka Police Department's lobby.

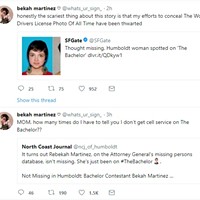

When the Journal began monitoring the AG's website in November of 2017, we compared several of its listings against any extra information we could find online. We were able to contact one of the reported missing — a mother and her 2-year-old daughter — via social media and ask why the Eureka Police Department had placed her on the database two months earlier. She had no idea and asked for information about how to remove the listing. We gave her contact information for the nearest law enforcement office and the listing disappeared shortly afterward. Another woman — Allison Nicole Strout — was listed as missing since May of 2016 but appears to have been active on social media the entire time. Her name was removed after she showed up in a Humboldt County Drug Task Force bust at a Eureka motel in October. These cases illustrate a small but frustrating subset of the data: Some people aren't actually missing and others just don't want to be found.

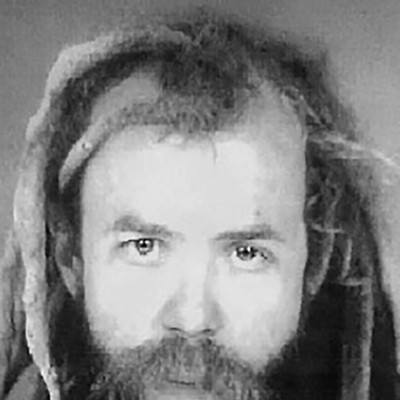

Young and other law enforcement professionals emphasize that Humboldt County is a good place to disappear. It's not unusual, they say, to spend resources searching for missing adults at the behest of friends, parents or spouses only to be told by the party in question that they had cut off contact for a good reason, such as estrangement or abuse, and were laying low out of choice. Many people come to the area to work in the cannabis industry, leaving town to work on remote mountains where there is no cell phone service. They may be out of communication for weeks or months, with family members only having a vague idea of where they might be that — they drove to Eureka, are in Humboldt County, or are in the general "Emerald Triangle" region. These cases can be particularly hard to investigate.

"No one wants to cooperate with a missing persons investigation," says Young of cannabis-related cases. "Many people from throughout the state, nation and world come to Humboldt County to work in the cannabis industry. They often times will not communicate with friends and family regarding their location, and/or they go off the grid for extended periods of time. Many of those individuals will return home and no one notifies law enforcement that they are no longer missing. Consequently, they remain in the data base. Some missing persons are victims of homicides with no apparent leads and lack of witness cooperation."

While law enforcement pointed to the local cannabis industry as a primary reason for Humboldt County's high rates of missing adults, its worth noting that our rates are still roughly double those of the rest of the Emerald Triangle — Mendocino and Trinity counties.

Eureka, as the county seat, becomes the default location for many missing persons reports. Brittany Powell, a crime analyst with EPD, says her agency takes about 40 reports a month, with a total of about 500 reports filed last year. Patrol officers take the initial report and, if there is any sign of suspicious circumstances, reach out to friends and family.

"Most of the individuals have been located and cleared from the system," Powell wrote the Journal in an email. "I would say most are found within a few days."

Many people reported missing to EPD are adults who were en route to the area when they last spoke to their family, or members of the homeless population who have fallen out of touch with their loved ones and are rumored to be in the area.

"These reports are usually for the long-term homeless community," Powell says. "Family members [sometimes after the passing of a loved one] try to get in touch with an estranged family member. A lot of the time it is not known how long the person was in Eureka, if at all. Also, the descriptions and information regarding the person are often minimal."

Both EPD and the sheriff's office enter missing persons into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), but only after a certain period of investigation. ("Once all potential leads have been exhausted," according to Young.) NamUs, a federal database of missing persons and unidentified bodies, connects each case with a caseworker who compares it against reports, looks for patterns and collaborates with families and local law enforcement. NamUs' website includes several Humboldt County area reports that don't appear on the Attorney General's website. This is not uncommon, according to NamUs' founder and Director Todd Matthews, who says the patchwork of information available through local and state organizations doesn't offer the full picture that a national registry might.

"I don't know what I don't know," says Matthews, who has been advocating for legislation to mandate all law enforcement agencies put missing persons reports into the national database. "I don't know why it isn't standardized. It might be a money thing but I say, we've already paid for it."

The NamUs system allows family members to submit DNA samples to its database for comparison against unidentified bodies (there are no unidentified bodies currently in the system for Humboldt County), and to also contact NamUs caseworkers to update information, refining descriptions and adding photographs. One of the names that appears on the NamUs website but not on the AG's list, Cody Conoboy, has been positively matched to a DNA sample. Conoboy, 15, was swept into the Trinity River after jumping out of a stolen car near Hoopa in January of 2011. A jawbone found the following September was positively identified Conoboy's in 2013. It's not uncommon for these cases to remain on the database, according to Young.

"Some of the people we will never be able to remove from the system," he says. "Maybe they were washed out to sea [in] a witnessed event but their bodies were not recovered."

Young says Conoboy's listing probably remains because the U.S. Department of Justice only removes a person whose body part has been recovered if the part is something they "can no longer live without," such as a skull.

Another case that remains on the NamUs database belongs to Claire Louise Christie, who was reported by her husband as lost at sea in 1977. That case gained new significance in 2010 when her husband, Ernest Samuel Christie Jr., was posthumously identified as the perpetrator of the 1988 torture and murder of Lysandra Marie Turpin. Christie was also implicated in the torture of several other women who, according to an interview with HCSO detective Steve Quenell in the Times-Standard, he would pick up in Eureka's Old Town and take back to his home in Fieldbrook. One was allegedly brought aboard Christie's fishing boat, where he duct taped her wrists and said she wouldn't be coming back. (She escaped.) Claire Louise Christie's fate may never be known.

Matthews says instances of people going missing for an extended period of time without something bad having happened are rare, although it does happen to the mentally ill and destitute.

"I know a guy who recently lost his cell phone because he couldn't pay for it," he says, adding that along with poverty, a lack of family or community can play a role in whether someone is declared missing or eventually found. "The biggest discrimination that exists is whether someone is expecting you to show up."

Many families who were expecting loved ones to call or return home from Humboldt County only to have them go missing find the process of searching for them to be frustrating. Vikki Joseph, whose brother Jeff Joseph disappeared in June of 2014, says that she has found community with other families whose loved ones disappeared, many of whom, like Jeff, were involved in the cannabis industry.

"It's hard to connect with anyone who understands what it's like to have a missing family member up there," Vikki Joseph says. Since Jeff went missing, she has corresponded with the families of Danielle Bertolini, Sheila Franks and Chris Giauque, all of whom disappeared under suspicious circumstances related to the cannabis industry. (Bertolini's remains were found in 2015.)

Jeff Joseph, a dispensary owner from Los Angeles, was visiting his farm near Weitchpec when he suddenly stopped returning calls from his sister and girlfriend. His cell phone last pinged off a tower near Bloody Camp Road near Hoopa. Vikki Joseph believes her brother was murdered in connection with his cannabis grow and says his partners were not cooperative with the sheriff's investigation, nor would they let his family access the property to gather Jeff's belongings. The partners allegedly told her brother and uncle that if they crossed the gate, they would be shot. She found their refusal to cooperate with her family or help investigators suspicious.

"Where I live is very suburban, it's not forest, it's not remote, we don't lose cell phone service," she says in a phone interview. "It can be very dangerous. When you mix growing big amounts of weed and lots of money, it's a recipe for disaster."

Trying to keep her brother's name in the public eye and communicate with investigators from so far away has been challenging. While segments like the Crime Watch Daily piece keep a laser focus on photogenic young women, little attention has been given to Jeff Joseph's case outside of local news sites like Redheaded Blackbelt and it remains unsolved four years later. But you won't find Jeff's case on the AG's listings for Humboldt County. Because Vikki Joseph made the report in Los Angeles, that's where the case is listed. She says she worked closely with Humboldt County Sheriff's Office detective Todd Fulton but received no notice when he retired, finding out only three months later that the case had bounced to a different detective. Vikki Joseph has ended up doing a lot of investigative work herself, tracking down leads and hiring private investigators.

The sheriff's office wouldn't comment on the specifics of the case, stating it was an open investigation, but Freese says if they had a new lead, they would work it. In general terms, Freese says that if they had enough probable cause to cross a locked gate, they would request a warrant and do so. In the case of Jeff Joseph, she says, there's a lot she just can't share.

"We've done extensive work on it," she says, adding that it's imperative for family members to keep in contact with the department and encourage others who might have information to come forward. "I think they should call over to our department and see who is carrying the case. Often it's going to be a family member, what they forgot to say or didn't think of [that helps]. I am all about having family members call. Sometimes I will set up a day, every week or every month. I say, 'I will call you at 9 o'clock,' and update them on where we're at. That can bring some peace."

Vikki Joseph isn't satisfied. She describes herself as being in a double-bind, with plenty of information but a frustrating lack of options for what to do with it.

"I have things other families don't have," she says. "Things that could have all been researched. But there's only so much we can do. I can research it and research it, can provide them with all their leads and tips but I can't arrest anyone."

Although Jeff Joseph was originally listed as "voluntary missing," Vikki Joseph doesn't believe her brother would have disappeared on purpose. He was a loving, kind man, she insists. He was non-violent, refusing to carry a gun. When their mother was dying, Jeff was the one who took care of her, feeding her and changing her diapers. He would never go this long without letting his family know he was OK. It hurts Vikki Joseph to think about what he must have felt in those last moments, the fear and betrayal. She just wants to know where his body is to bring him back to Los Angeles County.

Asked what she's going to do once that happens, Vikki Joseph doesn't hesitate.

"I'm going to put him to rest next to his mom," she says.

Journal graphic designer Jonathan Webster contributed to this report.

Linda Stansberry is a staff writer at the Journal. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter @LCStansberry.

Editor's Note: For more information about persons missing in the tri-county region, check out this story by Redheaded Blackbelt's Kym Kemp, with whom we collaborated for part of our reporting.

UPDATE: After this story went to print we received a call from one of the people on the Attorney General's list of missing persons, Daniel Ogden Stromberg, who says he is not missing but has, in fact, been living in Eureka for the past year. Stromberg was reported missing by his siblings in May 2017. We encouraged him to get in touch with them and notified the Eureka Police Department that he is safe and sound. For the full story, check out this link.

Comments (10)

Showing 1-10 of 10

more from the author

-

Lobster Girl Finds the Beat

- Nov 9, 2023

-

Tales from the CryptTok

- Oct 26, 2023

-

Graduation Day: A Fortuna Teacher Celebrates with her First Grade Class

- Jul 18, 2023

- More »

Latest in News

Readers also liked…

-

Through Mark Larson's Lens

A local photographer's favorite images of 2022 in Humboldt

- Jan 5, 2023

-

'To Celebrate Our Sovereignty'

Yurok Tribe to host gathering honoring 'ultimate river warrior' on the anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that changed everything

- Jun 8, 2023